Book Review: Gaining Much from “The Gift of Loss”

By Robert Waddell Journalist

Children of divorce or separation live a bifurcated life between their mother and father. They are often at odds with themselves, sometimes standing emotionally in the no-man’s land and mine field between warring adults. Their allegiances’ are torn and their love divided.

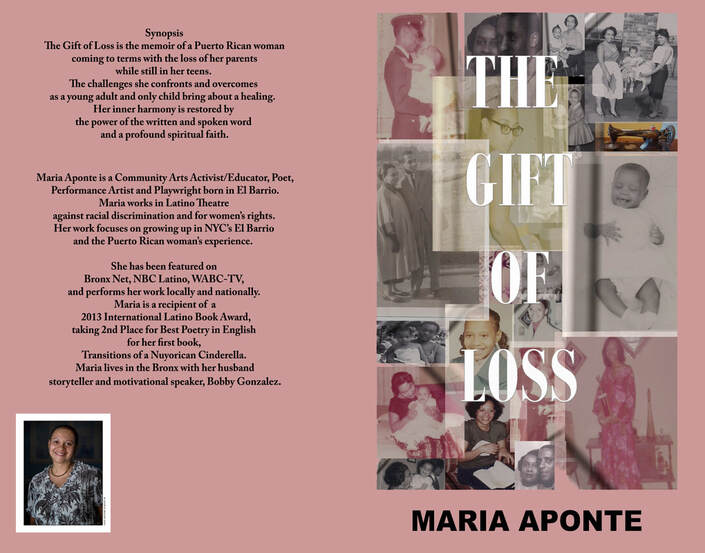

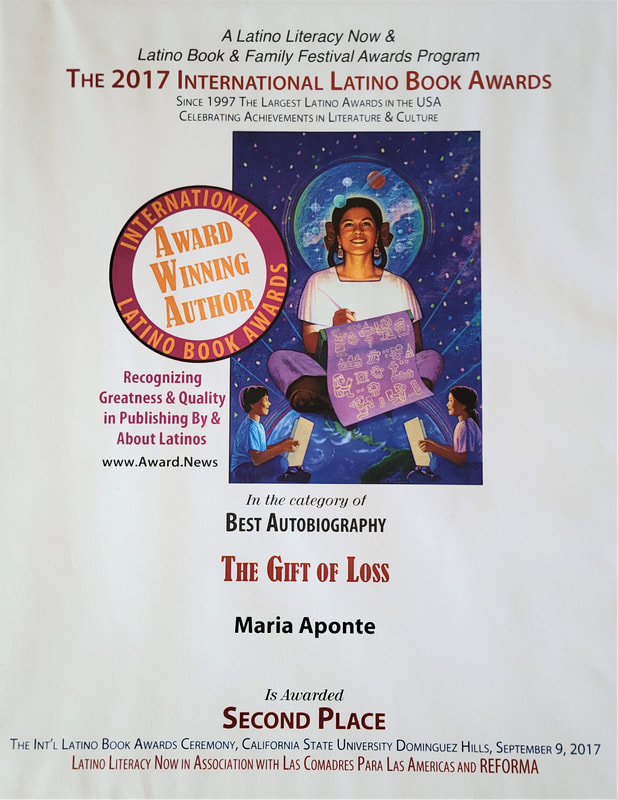

This is the case in Maria Aponte’s memoir “The Gift of Loss,” a combination of prose and poetry explaining how she grew up in and survived those two worlds, not Anglo and Latino, but a life anchored by each parent. Her father is the fun-loving musician who escapes with his daughter to Coney Island and her stern mother hell bent on making sure her daughter graduates school.

Told in five chapters, or five orchestral movements, or the five acts of a play, heavy subjects are treated with poise, dignity and a sense of serenity because in the end, Aponte, as a character, chooses both sides. When Aponte writes she captures the depth and nuisance of Puerto Rican life in all of its messy humanity. Her story is uniquely hers and at the same time transcends, gingerly and specifically, lives and iconography common to many Boricuas.

One of the most insightful statements in a book chock full of profundity is the start of Part Two, which reads “The day I forgave my parents was the day I started to grow up.”

It is through two serious traumatic losses, having to become independent, loss of control then finding salvation through poetry and art where “The Gift of Loss” takes off. This is a wonderful albeit short memoir of someone, very Puerto Rican and very universal, finding her place in the world.

Aponte’s writing hand gently touches on Boricua life without hyperbole, diatribe or polemics. She proves that the political is personal and the personal political.

She writes, “…on the evening of the New York blackout, July 13…As fires burned and the sound of shattered glass echoed in the streets of the Bronx, we could literally feel the community’s anger: a hot soup of poverty, racism, and hunger boiling over. Nobody seemed interested in turning down the flame on the stove.”

Aponte describes the 1970s but she could easily have been showing America in the early part of the 21st Century.

Orson Welles gets credit for saying that all humans are “born alone, live alone and die alone. We have people around us to give us the illusion that we’re not alone.” Aponte’s work evokes the filmmaker’s sentiments. Aponte also bring to mind the sentiments of author Carson McCullers who ushered in, through her Gothic Southern fiction, a sense of pain, estrangement and loss.

Life has a way of offering so much when young then begins taking things away as if one were a naughty child punished for having too much fun, a daisy plucked bald of its petals.

Aponte’s work is so very compact, short, and fresh while conjuring El Barrio and the Bronx of the 1970s and 1980s. This is a story of a young lady becoming a woman. Though the title may seem like an oxymoron, “The Gift of Loss” cleverly reveals the circular trajectory of achieving power from pain. Aponte brilliantly demonstrates that while loss may debilitate, it can also liberate. Aponte reveals how the body and soul can grow through struggle, and that one need not hold onto the pains of the past.

“The Gift of Loss” is a short read, with a lasting message. A story filled with so much history, culture, and sadness that also manages to provide hope and inspiration for the future.

By Robert Waddell Journalist

Children of divorce or separation live a bifurcated life between their mother and father. They are often at odds with themselves, sometimes standing emotionally in the no-man’s land and mine field between warring adults. Their allegiances’ are torn and their love divided.

This is the case in Maria Aponte’s memoir “The Gift of Loss,” a combination of prose and poetry explaining how she grew up in and survived those two worlds, not Anglo and Latino, but a life anchored by each parent. Her father is the fun-loving musician who escapes with his daughter to Coney Island and her stern mother hell bent on making sure her daughter graduates school.

Told in five chapters, or five orchestral movements, or the five acts of a play, heavy subjects are treated with poise, dignity and a sense of serenity because in the end, Aponte, as a character, chooses both sides. When Aponte writes she captures the depth and nuisance of Puerto Rican life in all of its messy humanity. Her story is uniquely hers and at the same time transcends, gingerly and specifically, lives and iconography common to many Boricuas.

One of the most insightful statements in a book chock full of profundity is the start of Part Two, which reads “The day I forgave my parents was the day I started to grow up.”

It is through two serious traumatic losses, having to become independent, loss of control then finding salvation through poetry and art where “The Gift of Loss” takes off. This is a wonderful albeit short memoir of someone, very Puerto Rican and very universal, finding her place in the world.

Aponte’s writing hand gently touches on Boricua life without hyperbole, diatribe or polemics. She proves that the political is personal and the personal political.

She writes, “…on the evening of the New York blackout, July 13…As fires burned and the sound of shattered glass echoed in the streets of the Bronx, we could literally feel the community’s anger: a hot soup of poverty, racism, and hunger boiling over. Nobody seemed interested in turning down the flame on the stove.”

Aponte describes the 1970s but she could easily have been showing America in the early part of the 21st Century.

Orson Welles gets credit for saying that all humans are “born alone, live alone and die alone. We have people around us to give us the illusion that we’re not alone.” Aponte’s work evokes the filmmaker’s sentiments. Aponte also bring to mind the sentiments of author Carson McCullers who ushered in, through her Gothic Southern fiction, a sense of pain, estrangement and loss.

Life has a way of offering so much when young then begins taking things away as if one were a naughty child punished for having too much fun, a daisy plucked bald of its petals.

Aponte’s work is so very compact, short, and fresh while conjuring El Barrio and the Bronx of the 1970s and 1980s. This is a story of a young lady becoming a woman. Though the title may seem like an oxymoron, “The Gift of Loss” cleverly reveals the circular trajectory of achieving power from pain. Aponte brilliantly demonstrates that while loss may debilitate, it can also liberate. Aponte reveals how the body and soul can grow through struggle, and that one need not hold onto the pains of the past.

“The Gift of Loss” is a short read, with a lasting message. A story filled with so much history, culture, and sadness that also manages to provide hope and inspiration for the future.

The Gift of Loss is available on Amazon.com

Transitions of a Nuyorican Cinderella is available on Amazon.com

Univision Review 2012

Bookmarked: Maria Aponte’s ‘Transitions of a Nuyorican Cinderella’

Aponte’s readings often have a musical component to them.

By ARTURO CONDE

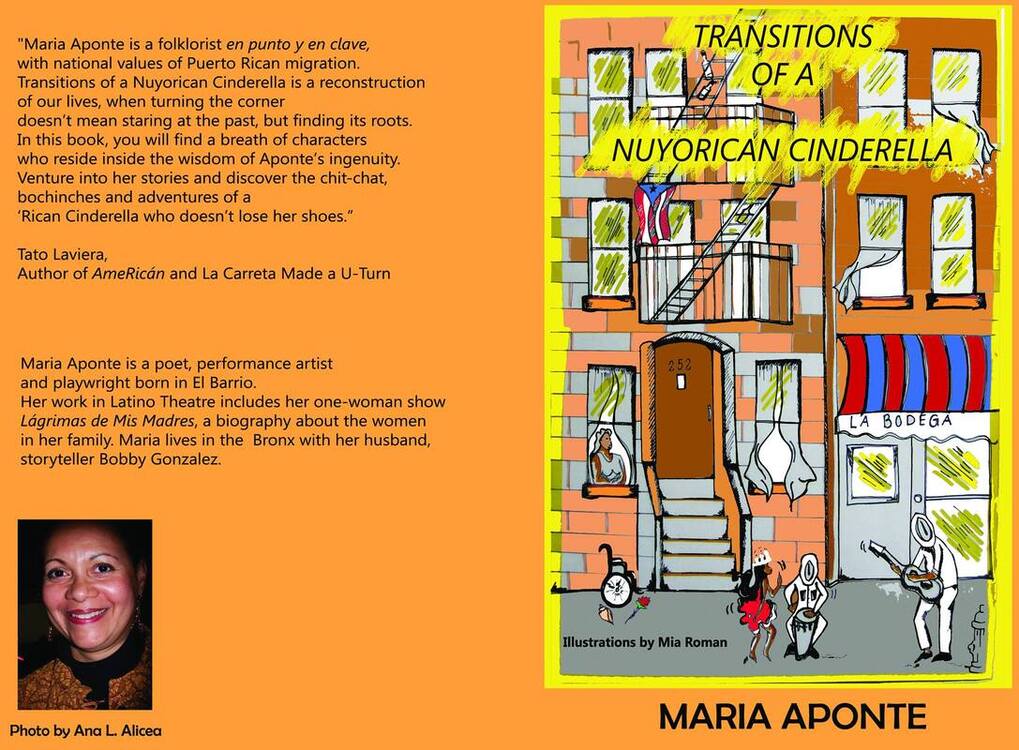

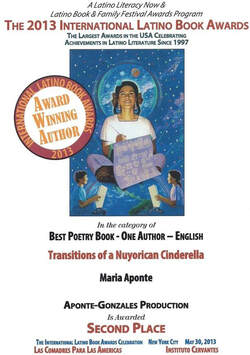

“The first time I put something to paper was with a #2 pencil, riding on the #4 train from the Bronx to Manhattan,” writes the Puerto Rican poet Maria Aponte in her first book, Transitions of a Nuyorican Cinderella. The year was 1979, and the paper was a brown bag from the bodega.

Aristotle said that poets, unlike historians, tell general truths about things that might happen. And Aponte’s lyrical narrative is like an epic poem that describes the possible lives of hundreds, if not thousands, of Latino immigrants who live in perpetual movement between their home countries and the United States.

Puerto Ricans, of course, are technically not immigrants; they are American citizens since 1917. But the experience of being uprooted economically, socially, and culturally from one place to another is the same.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, New York was a city where immigrants from different backgrounds were compelled to write the histories of their homelands. Preserving one’s origin was a prerogative in a cavernous and industrial metropolis where it was easy to lose one’s identity. And for Puerto Ricans, Transitions of a Nuyorican Cinderella will recall the spirit of other immigrant accounts, like the 1984 Memoirs of Bernardo Vega by Cesar Iglesias, which offers insightful descriptions of Boricua and Latino life in New York during the early 20th century.

Aponte’s book is a lyrical collection of poems, character and neighborhood profiles, and short stories about the Puerto Rican diaspora in New York. Aponte herself grew up a single child in 1960s East Harlem (“El Barrio”) and later, she moved to the Bronx in the 1980s, where she became a caregiver to her terminally ill mother. The theater became her safe place, and now in her mid-50s, Aponte is an accomplished poet, performance artist, and playwright; and an educator/academic counselor at Fordham University. Her one-woman show, Lagrimas de mis Madres, a biography of the women in her family, has toured the country since its debut in 1996.

Transitions of a Nuyorican Cinderella opens with the narrative poem “Cruce el Agua,” which describes the primal instinct that draws immigrants back to their homeland. The protagonist, who is later identified as Rosa, could be any small town Puerto Rican housewife who migrated during the 20th century to the Lower East Side and Spanish Harlem in Manhattan, or further north to other enclaves in the Bronx. Squeezing small gandule beans in her palm, Rosa feels the weight of her life bending her shoulders as she contemplates leaving her small town of Coamo in Puerto Rico for New York, and she wrestles with the obligation of maintaining the traditions that she inherited directly from her mother. But it is at that extreme moment of vulnerability that she makes a heroic promise to never forget her family’s finca in Coamo, and resolves like many other Latino mothers to mine her children’s imagination and education in New York with stories of Puerto Rico.

At times, Aponte’s book reads like the universal story of all immigrants in spite of cultural differences. In “The Clothesline of the Rosas,” a Puerto Rican and an Italian immigrant in Spanish Harlem are able to find common ground in their everyday household chores. Aponte describes the creaking sound that the clotheslines make when the women pull their laundry in as a coded message that helps them understand their shared plight as immigrants.

In her first book, Aponte offers a colorful collection of poems and prose on the Puerto Rican diaspora in New York.

Aponte also describes the displacement that many immigrants feel after they are uprooted from their homes and culture. In the poem “Abuela’s Plant,” a houseplant growing from eggshells, old Café Bustelo coffee grinds, water, and sunshine helps the narrator regain a sense of familiarity, comfort, and faith, in a concrete and asphalt city that is otherwise impersonal to her.

Other lyrical profiles and character sketches are like small colored tiles in a much larger mosaic that depicts the solitude, introspection, sadness, and hope of all immigrants. Aponte describes the wrinkled but dedicated hands of a Puerto Rican woman flowing gently through white flour to make dough, while she simmers meat with tomato sauce, sofrito and recao to satisfy the demanding appetite of her husband. In another sketch, the poet describes a woman who recalls being driven with her girlfriends in polished Cadillacs, Pontiacs, and Thunderbirds to concert halls where they danced to popular mambos, cha-chas, and boleros that were popular during the 1950s and 1960s.

But perhaps the moment that will resonate most with Latino readers is described in the narrative street life sketch “A Question.” When a man challenges the protagonist’s Puerto Rican identity because she looks black, the woman captures poetically how Latinos do not have only one culture or race but many: “I am a mixture of spices grown in warm, rich climates. I am the smell of tropical flowers that grow in lush green hills. I am Indian. I am African. I am Spaniard.”

The greatest accomplishment of Aponte’s book is how it finds beauty in modest places, and it preserves and exalts the dream of a better life for younger generations of Latino immigrants. In the short story “White Carnations,” which closes the book, Aponte reimagines New York through the lens of a fairy tale: “Once upon a time, in a land far away, there was a small kingdom called the Bronx.” In this story, Linda arranges white carnations that remind her of the brilliant stars in the summer night sky. Those stars reflect the dreams of thousands if not millions of Latino immigrants who yearn to escape from the hardships of everyday life. And by the end of the tale, Linda is transformed from a lonely, marginalized woman to a modern day Cinderella who dances slowly with her tall dark prince Carlos at the Hunts Point Palace in the Bronx.

As for why she decided to go with a fairy tale theme, Aponte explains on this recent interview on BronxNet Community TV that she wanted to honor Latina women. “I wanted us to be there, that’s always been my work, even when I started in theater in the 70s.”

Lagrimas de Mis Madres written and performed by Maria Aponte

Lagrimas de Mis Madres an autobiographical play based on my life growing up in New York City’s El Barrio, East Harlem in the 1960’s during the Civil Rights Movement. It is the three generational story told through the eyes of the current generation about her Mother and Grandmother. Originally commissioned as part of a performance piece, called Tides of Intolerance produced by ShotGun Productions that showcased four different works by women of color against oppression. Lagrimas de Mis Madres debuted at the Asia Society in 1996. And continued to be performed nationally at colleges and universities and at the Julia de Burgos Cultural Center in East Harlem.

Photo Credit: Elena Mamarazzi Marrero.

I Will Not Be Silenced written and performed by Maria Aponte

I Will Not Be Silenced based on the life of Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz

I Will Not be Silenced based on Octavio Paz’s biography The Traps of Faith on the 17th century Mexican writer and feminist nun Sor Juan Ines de la Cruz. A one act play that focuses on Sor Juana’s famous letter defending her right to an education and knowledge called Respuesta a sor Filotea de la Cruz. I Will not Be Silence has been performed nationally at various colleges and universities such as Loyola Chicago, Vassar College, Hamilton College and most recently for the Upward Bound Program for Montclair University. This performance piece includes a follow up discussion about Sor Juana for students and faculty.